![Beware of NFL Rules For Instances When There Are No Rules [PHOTOS, VIDEO]](http://townsquare.media/site/183/files/2012/01/136100538.jpg?w=980&q=75)

Beware of NFL Rules For Instances When There Are No Rules [PHOTOS, VIDEO]

Ever wonder what happens when something obviously unfair yet not specifically covered by the rules happens during a football game?

According to NFL rules, a referee can award points for "palpably unfair acts." Here, thanks to quirkyresearch.blogsot.com, are some possible situations where it could actually happen.

The palpably unfair act rule gives the referee full discretion to decide what should happen when such events occur, up to and including awarding one team a score.

The following is a survey of the NFL rules pertaining to palpably unfair acts, and the occasions when they might have (or in the case of two college games, have) been called.

(Note: to my knowledge, there has never been a ruling of a palpably unfair act in the NFL. The NCAA rules are similar enough that college games are included below.)

Rule 5-2-8-c: Penalties for illegal substitution or withdrawal … for interference with the play by a substitute who enters the field during a live ball: Palpably unfair act (see 12-3-3)

Rule 11-2-1-e: A touchdown is scored when … the Referee awards a touchdown to a team that has been denied one by a palpably unfair act.

Rule 12-3-3: A player or substitute shall not interfere with play by any act which is palpably unfair. Penalty: For a palpably unfair act: Offender may be disqualified. The Referee, after consulting his crew, enforces any such distance penalty as they consider equitable and irrespective of any other specified code penalty. The Referee could award a score.

Great Lakes Naval Training Station at Navy, November 23, 1918: (In the Great Lakes starting lineup: future NFL Hall of Famers George Halas and Paddy Driscoll.)

With around three minutes to go, Navy, up 6-0, had the ball on the Great Lakes 8 yard line. Navy’s Bill Ingram fumbled on a plunge into the line, and the ball popped into the hands of Great Lakes’ Lawrence Eielson, who had a clear path down the Navy sideline to the end zone.

William Hardin Saunders (the same “Navy Bill” Saunders who would later coach at Clemson and Colorado) was warming up on the Navy sideline. Saunders inexplicably came off the bench to tackle Eielson at the Navy 30. (Even 30 years later, all Saunders would say was that he didn’t care to discuss his motivation. His coach, Gil Dobie, claimed that Saunders was unconsciously obeying Dobie’s ‘tackle him, tackle him’ shouts.)

Later stories differ as to what happened next. Most credible is referee Harry Heneage’s account as reported in the Chicago Tribune a few days later. According to Heneage, “I gave [Great Lakes captain Emmett] Keefe the ball and told him to touch it down back of the goal and then allowed the try at goal,” thus awarding Great Lakes the touchdown. Great Lakes then kicked the extra point, and held on for a 7-6 victory.

The NCAA rules at the time did not permit awarding a score for a palpably unfair act. (Rule XXIII, Section 11: “In case the play is interfered with by some act palpably unfair and not elsewhere provided for in these rules, either the Referee or the Umpire shall have the power to award 5 yards to the offended side, the number of the down and the point to be gained [line of gain, e.g. first down marker] being determined as provided in Rule XXV.”) Technically, it should have been either a 15 yard penalty for unsportsmanlike conduct or a 5 yard penalty for a palpably unfair act not covered by the rules. However, Navy did not protest Heneage’s decision.

At some point between 1921 and 1954, “[A touchdown is to be awarded when] anyone other than a player or official … tackles a runner who is in the clear and in his way to a reasonably assured touchdown” was added to the approved rulings section of the NCAA rulebook.

Rice v. Alabama, Cotton Bowl, January 1, 1954:

Rice, up 7-6, had the ball on its own 5 yard line. Dicky Maegle (nee Moegle) swept around right end and streaked down the Alabama sideline. Alabama’s Bill Oliver had a possible angle to stop Maegle; otherwise there was no one between him and the end zone.

Alabama’s Tommy Lewis, “too full of ‘Bama’” (as he later explained), jumped off the bench and knocked Maegle down at the Alabama 40.

Within seconds, referee Cliff Shaw, pointing to Lewis and the bench, awarded a touchdown to Rice. Maegle was credited with a 95-yard TD run.

Lewis was not ejected. Starting in 1955, players coming off the sideline to make a tackle would be automatically disqualified.

Rule 13-1-7: A non-player shall not commit any act which is palpably unfair. Penalty: For a palpably unfair act, see 12-3-3. The Referee, after consulting the crew, shall make such ruling as they consider equitable (15-1-6 and Note) (unsportsmanlike conduct).

Note: Various actions involving a palpably unfair act may arise during a game. In such cases, the officials may award a distance penalty in accordance with 12-3-3, even when it does not involve disqualification of a player or substitute. See 17-1.

Virginia Tech at Virginia, November 18, 1995:

On the last play of the game, Virginia was intercepted by Virginia Tech’s Antonio Banks. Virginia trainer Joe Geick stuck his leg out, seemingly to trip Banks, as Banks ran down the sideline for the add-on score.

Pittsburgh Steelers at Jacksonville Jaguars, September 22, 1997:

With the Steelers down 23-21, Norm Johnson’s last-second 40-yard field goal was blocked by Travis Davis and bounced towards the Steelers’ sideline and coach Bill Cowher.

Cowher stepped on the field (he later claimed that he was planning to kick the ball in frustration), but the Jaguars’ Chris Hudson recovered the ball and ran towards the end zone. Cowher cocked his forearm as if to punch Hudson but at the last moment stepped back while Hudson ran past him for a touchdown.

Had Cowher kicked the loose ball, it is unclear what the refs would have done; had Cowher punched or tackled Hudson, it is likely that they would have awarded the Jaguars a touchdown. (Of note: the Jaguars were favored by 4 points.)

Rule 12-3-1-s: [Unsportsmanlike conduct] specifically include[s] … Goal-tending by a defensive player leaping up to deflect a kick as it passes above the crossbar of a goalpost …. The Referee could award three points for a palpably unfair act (12-3-3).

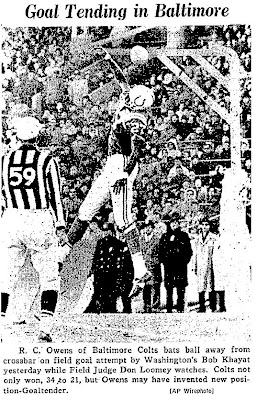

Washington Redskins at Baltimore Colts, December 8, 1962:

6’3” Colts wide receiver R.C. Owens (better known for popularizing the Alley-Oop pass, in which the receiver outjumps the defenders) blocked a 40-yard field goal at the crossbar. At the time, this was legal.

The above rule (which appears to allow catching a field goal at the crossbar) was enacted before the 1963 season.

(Note: as best I can tell,, the AFL did not enact a similar rule. More confusingly, there are numerous reports of the Chiefs' 6'9" Morris Stroud leaping for and barely missing a George Blanda field goal in 1970, the year after the NFL-AFL merger. Research in progress.)

Rule 17-1-1: If any non-player, including photographers, reporters, employees, police or spectators, enters the field of play or end zones, and in the judgment of an official said party or parties interfere with the play, the Referee, after consulting his crew, shall enforce any such penalty or score as the interference warrants.

Miami Dolphins at New England Patriots, December 12, 1982:

The Snow Plow Game.

San Francisco 49ers at Denver Broncos, November 11, 1985:

On a snowy Monday night in Denver, the 49ers, trailing 14-3, lined up for a 19-yard field goal at the end of the first half. Just as the ball was being snapped, a snowball thrown from the crowd landed in front of holder Matt Cavanaugh, distracting him enough to cause him to fumble the snap.

Jim Tunney, referring the game, did not call for the down to be replayed. A day later, he claimed to the Associated Press that “we have no recourse in terms of a foul or to call it on the home team or the fans. There’s nothing in the rule book that allows us to do that.” Tunney also explained to Art McNally, the head of NFL officials, that the snowball did not hit Cavanaugh or 49ers kicker Ray Wersching, and that Cavanaugh showed no change in concentration, not even flinching.

McNally added, “There is no provision in the rule book specifically for snowballs, or any objects, unless they strike the players. However, the referee is empowered to make any decision that is not specifically covered by the rules.”

Others, most prominently Tex Schramm, president of the Dallas Cowboys and head of the NFL competition committee, believed the play should have been stopped at the instant the snowball disrupted the play.

Schramm: “It should be like baseball. If a balloon or a piece of paper or something that can distract a player comes on the field, they immediately signal time out. We stop games for dogs. You can’t have something like that. Next time, it’ll be a beer bottle or a whiskey bottle.”

Bill Walsh, 49ers coach: “The way to stop [similar fan behavior] would be to replay the play. Then there would be no more snowballs ever. By allowing it to affect a very important play and say their hands are tied – [the officials] are just inviting the riotous action of fans.”

Tom Landry, Cowboys coach: “When something like that is so obvious to both sides, you shouldn’t be penalized by the fans.”

Hugh Campbell, Falcons coach: “They should replay it. And if another snowball comes down, they should award them a field goal.”

The 49ers lost the game 17-16 and finished 10-6, 1 game behind the Los Angeles Rams in the NFC West.

Rule 17-2 - Extraordinarily Unfair Acts:

Article 1 - The Commissioner has the sole authority to investigate and take appropriate disciplinary and/or corrective measures if any club action, non-participant interference, or calamity occurs in an NFL game which he deems so extraordinarily unfair or outside the accepted tactics encountered in professional football that such action has a major effect on the result of the game.

Article 2 - The authority and measures provided for in this entire Section 2 do not constitute a protest machinery for NFL clubs to avail themselves of in the event a dispute arises over the result of a game. The investigation called for in this Section 2 will be conducted solely on the Commissioner’s initiative to review an act or occurrence that he deems so extraordinary or unfair that the result of the game in question would be inequitable to one of the participating teams. The Commissioner will not apply his authority in cases of complaints by clubs concerning judgmental errors or routine errors of omission by game officials. Games involving such complaints will continue to stand as completed.

Article 3 - The Commissioner’s powers under this Section 2 include the imposition of monetary fines and draft-choice forfeitures, suspension of persons involved in unfair acts, and, if appropriate, the reversal of a game’s result or the rescheduling of a game, either from the beginning or from the point at which the extraordinary act occurred. In the event of rescheduling a game, the Commissioner will be guided by the procedures specified in Rule 17, Section 1, Articles 5 through 11, above. In all cases, the Commissioner will conduct a full investigation, including the opportunity for hearings, use of game videotape, and any other procedure he deems appropriate.

Spygate. The Patriots were fined $250,000 and lost a first-round draft pick, and coach Bill Belichick was fined $500,000 for illegally taping the Jets' defensive signals. This may very well have been considered an extraordinarily unfair act during a game, and the Patriots' punishment fits within Rule 17-2-3, but the NFL's public statements on the matter are unclear.

Rule 12-3-2: The defense shall not commit successive or continued fouls to prevent a score. Penalty: For continuous fouls to prevent a score: If the violation is repeated after a warning, the score involved is awarded to the offensive team.

(NCAA) Rule 9-2-3 Unfair Acts

The following are unfair acts:

a. A team refuses to play within two minutes after ordered to do so by the referee.

b. A team repeatedly commits fouls for which penalties can be enforced only by halving the distance to its goal line.

c. An obviously unfair act not specifically covered by the rules occurs during the game (A.R. 4-2-1-II).

PENALTY—The referee may take any action he considers equitable, including assessing a penalty, awarding a score, or suspending or forfeiting the game.

Penn State at Wisconsin and North Dakota State at Cal-Davis, November 4, 2006:

Before the 2006 season, the NCAA instituted several rules designed to shorten the time of games. Among these were Rule 3-2-5, starting the clock on kickoffs as soon as the ball was kicked off (as opposed to touched in the field of play), and Rule 3-2-5-e, starting the clock after changes of possession on the ready-for-play signal (as opposed to on the snap).

The rules were, at best, poorly thought out, and easily exploited.

Wisconsin scored a touchdown with 23 seconds left in the first half. On the ensuing kickoff, Wisconsin’s entire coverage team was 10 yards offside, eliminating any possibility of a real return while running the clock down to 14 seconds; the same thing happened on the re-kick, bleeding the clock down to 4 seconds. On the third kickoff, officials did not start the clock until Penn State had touched the ball, but time expired by the end of the runback (which Penn State fumbled). (Play-by-play)

Wisconsin coach Bret Bielema was unapologetic. "It worked exactly as we envisioned it. It's something we practice.

"Basically we wanted to put ourself in position that we wanted to have the maximum coverage that we could. We know they were going to try to return it for a touchdown, so we just did something that allowed us to have maximum coverage. They had the right either accept or decline the penalty. When they accepted it that means we're going to go back and do it all over again."

(The video has been pulled from YouTube; for the full flavor of the play and people's reactions to it, click here and scroll to comment 130 and read down.)

North Dakota State coach Craig Bohl was watching on television, and had his team do the same with 4 seconds remaining in a 28-24 win.

Unsurprisingly, the clock rules were changed again in the offseason.

For more, go to quirkyresearch.blogsot.com

![Yes, Angels in the End Zone. I'd rather use a picture from The Last Boy Scout, but the possession and use of guns on the field is covered under Rule 12-3-1-f. '[Unsportsmanlike conduct] specifically include[s] ... possession or use of foreign or extraneous object(s) that are not part of the uniform during the game on the field or the sideline, or using the ball as a prop.'](http://3.bp.blogspot.com/_Y2VUJqZ8YCg/Sxa7svCk3oI/AAAAAAAAAD4/Y2PUjP_1KPM/s400/AngelsEndZone2.jpg)